Thursday, April 30, 2009

Helpless

There is a town in north Ontario,

With dream comfort memory to spare,

And in my mind

I still need a place to go,

All my changes were there.

Blue, blue windows behind the stars,

Yellow moon on the rise,

Big birds flying across the sky,

Throwing shadows on our eyes.

Leave us

Helpless, helpless, helpless

Baby can you hear me now?

The chains are locked

and tied across the door,

Baby, sing with me somehow.

Blue, blue windows behind the stars,

Yellow moon on the rise,

Big birds flying across the sky,

Throwing shadows on our eyes.

Leave us

Helpless, helpless, helpless.

Comment: Whenever I hear this beautiful, mournful song I can't help but listen to the words. Isn't it funny how there are some songs where you never notice the words and others you can't help but? Maybe it's that certain words in the poem really catch a listener's attention like "north Ontario". How often do you hear that part of the world referenced? I also love "And in my mind/I still need a place to go,/All my changes were there." It's unexplainable how certain places live within a person's poetic memory. I haven't been to my childhood home in Pennsylvania for over five years now, but still whenever I dream of "home" I dream of my bedroom there. It's so locked within my psyche, that when I have a dream about seeing my parents again I never dream about their home in Boulder, I always dream about our house in Pennsylvania. It's strange how the details of my childhood bedroom are so vivid and second-hand.

I still wonder about the dirge-like chorus. What does he mean that he is left "helpless, helpless, helpless", in the face of these memories of nature and place? I'm not quite sure what it all means. Thoughts?

I love this song so much I've thought about trying to learn it on guitar, but there is a part of me that does not think I could do it a shred of justice. I'm sure countless people have tried to describe the unique nature of Neil Young's voice, but there is something about his delicate and fragile, falsetto-like warble combined with the lyrics that make this song poignant. Needless to say, my voice is nowhere near as expressive. It might be one of those songs that's better left to someone else to sing. And I'm just meant to listen.

If you actually want to hear the song, it was first recorded on the Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young album Déjà Vu. I first heard it on a greatest hits album called So Far. I wish I knew how to upload sound files to the blog, but alas I do not. Also, we don't yet have this album downloaded. But you might be able to hear a sample free on amazon or elsewhere or you can always buy it from itunes.

Art

Art

is a quality of attention,

the way color says how

light feels: yellow for the

aerosol of happiness, black

for the zero of what isn't;

the way light lined up right,

can cut through steel. Anything

is art if the mind's flawed right:

how soup feels being stirred,

how silence, broken open just so,

releases its essence and graces

the mind as a mint leaf in the air.

It's those who can't understand and

are dumbfounded by the obvious,

who thrive on on dissonance and

subverting the ordinary into the

extraordinary who end up being

artists. What good is that, you ask?

No practical use as far as I can see.

In fact, Archimedes could've been

bragging about art's uselessness when

he said "Give me a long enough lever,

a place to stand, and I will lift the earth."

Comment: Meyers is a Texas poet who was state laureate and now teaches at Southern Methodist University. I especially liked "Anything/is art if the mind's flawed right:/how soup feels being stirred/how silence, broken open just so,/releases its essence and graces

the mind as a mint leaf in the air./"

I have to admit...my grasp of classical references is very limited. I thought at first he was referring to Achilles and then realized Archimedes was someone different. In case of you are as classically challenged as me, Archimedes, who was Greek, was considered the greatest scientist/mathematician of antiquity. He also is regarded as developing the principle of the lever, as referenced in the poem.

Thursday, April 23, 2009

The Hardest Question

(essay taken from O's Big Book of Happiness)

How do you not abandon God when it feels as though God has abandoned you?

As a divinity student, I spend my time in a state of near perpetual confusion. I have not read a tenth of what my classmates have. Immanuel Kant and Friedrich Schleiermacher were the friends of their youth the way the Bionic Woman and Marie Osmond were the friends of mine. And my theological vocabulary, compared to that of my peers, is so impoverished as to make me practically a divine mute.During my second semester, I took a course on literature and theology, and at one of the first few sessions I woke from a daydream to discover that my classmates were eagerly discussing The Odyssey. I panicked, figuring that even though for once I had done the reading, I had done the wrong reading. But when I fiddled in my notebook to check the syllabus, The Odyssey was nowhere to be found. I poked my neighbor at the seminar table, gently, in the rib. “We were supposed to read The Odyssey?”

“Huh?” she said. “What are you talking about?” When I'm not in class, I work as a pediatrician, and I noticed pretty early that though divinity school, like pediatrics, is full of large-hearted, patient people, during intense intellectual discussions my fellow students can get a little testy.

“Why are we talking about The Odyssey?”

“Not The Odyssey,“ she said. “The Odyssey. Leibniz. Bayle. Polkinghorne. Those guys.”

“Oh,” I said, but she could tell I was still confused, so she wrote the word on my notebook, which was blank except for a half-finished doodle of a pony.

Theodicy.

“Oh,“ I said, as if I recognized the word. The class discussion moved on without my ever deciphering what exactly they were talking about—everyone lamenting the problem of theodicy without ever saying what it was—so I walked to the library after class to consult the dictionary and discovered that, like anyone who has ever felt afflicted by existence, I was already familiar with the concept, if not the word. It means an attempt to reconcile a God who is thoroughly and supremely good with the undeniable fact of evil in the world. It was as strange and embarrassing as the episode in class had been, to stand there and learn a word I suddenly felt I should have known all my life.

You don't have to have your cookies stolen in kindergarten too many times before you start to perceive that all is not right with the world. My cookies were stolen so often that I learned to offer them before they were demanded; my tormentor was a girl whose name I have long forgotten but whose face, round and sweet and utterly at odds with her dreadful disposition, has remained with me forever. I was raised Catholic, but was at that age more a dreamy little pagan, and it was indicative of my particular brand of religiosity that I prayed to Big Bird and not to Jesus to deliver me from my freckled oppressor. When nothing changed, I continued to believe in Big Bird, but I gave up on the notion that he cared very specifically about what happened to me.

The Value of Perseverance

As I became an older child and then a teenager, and dogs died and family members died and did not return to life no matter how hard I prayed to alter the fact of their death, I reconciled miserable reality with faith in an all-powerful and entirely benevolent God by telling myself that it wasn't that God didn't care to intervene, or didn't have the power to—my grief was just too particular to attract his attention. And as I grew still older and began to notice that we are accompanied throughout history by all sorts of unspeakable suffering, I amended this view, too, telling myself that the sum of these miserable parts must add up to something I could never apprehend while alive, and that although the fact of evil in the world might speak against God's scrutability, it said nothing about his existence or beneficence. But the older I became, and the more unhappy a place the world revealed itself to be, the more difficult it became to accept the idea of a personally invested, personally loving God.

Most days it's not the most pressing question in the world—how God can be good and allow terrible things to occur. It's when something really bad happens to you, or collective cataclysm descends, or some really wretched piece of news falls out of the television or slithers from the papers that this question that has vexed generations becomes all of a sudden quite present and personal. I would venture to guess that there are certain obsessive sorts of personalities who dwell on it even on sunny days and during Disney ice shows (maybe even especially during Disney ice shows), but for people with certain jobs—theologian, divinity student, vice detective, physician—it becomes a professional hazard. By the time I got to residency, I understood that I needed to come up with an answer to the question people kept asking when I told them I wanted to be a pediatric oncologist: “How can you stand to work in a field where you see such terrible things?”

I did see terrible things, but in fact it was those terrible things that seemed to enable me to get up and go back to work every day. If the parents and children who were actually suffering with the illnesses could be as gracious as I discovered them to be, the very least I could do was get myself back to the hospital to be with them as they labored through the process of getting well or dying. Sometimes it seemed that the failure of drugs or technology reduced the practice of medicine to a ministry of accompaniment. I say reduced, but you could argue that it's an elevation of our practice as physicians. I came to divinity school largely because I thought the experience and education would make me better able to accompany patients into their adversity, and I think I'm in the right place for that. But it turns out that I have already learned things as a doctor that make me if not a smarter divinity student, at least a less agitated one.

Fate and Faith

Every parent and child I meet who overcomes or succumbs to illness is challenged to reconcile their fate with their faith in the goodness of the world. They never reason or parse like theologians, and by no means do they all express a faith in any kind of God, but they all find strength and will to wake up every day to a job tremendously more difficult than mine. A child complains one morning at the breakfast table of numbness in one arm, and then collapses from a catastrophic cerebral bleed (or pulls a steaming rice cooker down upon her head, or rides a scooter headfirst into a speeding taxi), and a parent's world suddenly collapses. It's a privilege and a burden to be witness to other people's tragedies, to watch them proceed from stunned disbelief to miserable acknowledgment to stoic acceptance and then beyond to the place I can't quite enter myself, a place in which they are both fully aware of how completely horrible life can be and yet still fully in love with it, possessed of a particular buoyancy of spirit that is somehow heavier than it is light.

I can't say if I believe in the God who knows us and cares for us down to the last hair of our head, and so I don't feel obligated to reconcile such a being with the ugly facts of the chromosomal syndrome trisomy 13, or teenage myelogenous leukemia, but I am pretty sure one need look no further than people's responses to adversity to find evidence that there is something in the world that resists tragedy, and seeks to overturn the evils of seeming fate.

The last and least of my professions, after physician and student, is fiction writer, and I'd like to think that the little tragedy-resisting organ in me is the one that generates stories. They are ghastly, depressing stories for the most part, about ghosts, and zombies, and unhappy angels managing apocalypses, and people attempting to bring the dead back to life, but they are a great comfort to me. I write fiction mostly to try to make sense of my own petty and profound misery, and I fail every time, but every time I come away with a peculiar sort of contentment, as if it was just the trying that mattered. And maybe that's the best answer to the patently ridiculous problem of trying to reconcile all the very visible evil and suffering in the world with the existence of a God who is not actually out to get us: We suffer and we don't give up.

Chris Adrian's second novel, The Children's Hospital, was published by McSweeney's. He is a pediatrician and divinity student in Boston.

Comment: Okay. I know what you're all thinking: Casey has lost the plot. Yes, I did check out "O's (as in OPRAH) Big Book of Happiness" from the library. I've gotten acquainted with O Magazine sitting in waiting rooms and have come to appreciate it. It's very essay-driven and is all about living "your best life." Although this seems commercial (the great O has trademarked the phrase and all), it's as good a mantra to live by as any, no?

Anyway, I really enjoyed this essay because the end made sense to me. It still hasn't completely convinced me that God is good or even that there is a God, but it points out a truth: in the face of insurmountable tragedy people do try to survive with grace and dignity and meaning. We are more than just cells and function. We not only try to preserve our bodies and our mere survival, we try to preserve our spirit. We know instinctively that if our spirit dies, then the rest is dust as well.

Also, I am in awe of people who choose careers like pediatric oncology. It's like facing your worst fears and demons every day. But thank goodness there are people who have the courage to do it. I don't know where they find the strength and the fortitude, but I am grateful for it.

Wednesday, April 22, 2009

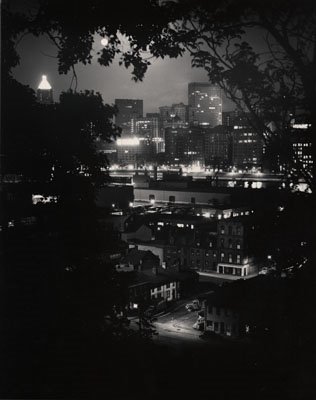

Oh, how I wish I lived in San Francisco...

You have to go to this fabulous exhibit at the Fraenkel Gallery for all of us. The exhibit is called “Edward Hopper & Company”. It illustrates how Edward Hoppers paintings influenced later 20th century photographers like Walker Evans and Stephen Shore. I'm intrigued by this idea because Hopper is one of my favorite painters (the Off Hesperus logo is a Hopper painting called "House at Dusk") and lately I've been reading a lot about photographers from the 60s and 70s like Stephen Shore, William Eggleston and Robert Frank. It shouldn't surprise me that links have been made between the two aesthetics. People are probably drawn to Hopper in the same way they are drawn to these photographers.

Just drawing a quick comparison between Hopper and Stephen Shore, they both focus on mundane settings and ordinary people. The subjects in their work (whether it be a person or a building) seem lonely and abandoned. And yet while desolate, there is a beauty in the desolation. The penetrating late afternoon sun on a a city building, lonely people sitting at a bar late at night, a pancake breakfast for one at a roadside diner. These are sad, indelible images.

E! I might have to make a return trip to San Francisco!

Sunday, April 19, 2009

Sunday Morning

I

Complacencies of the peignoir, and late

Coffee and oranges in a sunny chair,

And the green freedom of a cockatoo

Upon a rug mingle to dissipate

The holy hush of ancient sacrifice.

She dreams a little, and she feels the dark

Encroachment of that old catastrophe,

As a calm darkness among water-lights.

The pungent oranges and bright, green wings

Seem things in some procession of the dead,

Winding across wide water, without sound.

The day is like wide water, without sound,

Stilled for the passing of her dreaming feet

Over the seas, to silent Palestine,

Dominion of the blood and sepulchre.

II

Why should she give her bounty to the dead?What is divinity if it can come

Only in silent shadows and in dreams?

Shall she not find in comforts of the sun,

In pungent fruit and bright, green wings, or else

In any balm or beauty of the earth,

Things to be cherished like the thought of heaven?

Divinity must live within herself:

Passions of rain, or moods in falling snow;

Grievings in loneliness, or unsubdued

Elations when the forest blooms; gusty

Emotions on wet roads on autumn nights;

All pleasures and all pains, remembering

The bough of summer and the winter branch.

These are the measures destined for her soul.

III

Jove in the clouds had his inhuman birth.No mother suckled him, no sweet land gave

Large-mannered motions to his mythy mind.

He moved among us, as a muttering king,

Magnificent, would move among his hinds,

Until our blood, commingling, virginal,

With heaven, brought such requital to desire

The very hinds discerned it, in a star.

Shall our blood fail? Or shall it come to be

The blood of paradise? And shall the earth

Seem all of paradise that we shall know?

The sky will be much friendlier then than now,

A part of labor and a part of pain,

And next in glory to enduring love,

Not this dividing and indifferent blue.

IV

She says, "I am content when wakened birds,Before they fly, test the reality

Of misty fields, by their sweet questionings;

But when the birds are gone, and their warm fields

Return no more, where, then, is paradise?''

There is not any haunt of prophecy,

Nor any old chimera of the grave,

Neither the golden underground, nor isle

Melodious, where spirits gat them home,

Nor visionary south, nor cloudy palm

Remote on heaven's hill, that has endured

As April's green endures; or will endure

Like her remembrance of awakened birds,

Or her desire for June and evenings, tipped

By the consummation of the swallow's wings.

V

She says, "But in contentment I still feelThe need of some imperishable bliss.''

Death is the mother of beauty; hence from her,

Alone, shall come fulfilment to our dreams

And our desires. Although she strews the leaves

Of sure obliteration on our paths,

The path sick sorrow took, the many paths

Where triumph rang its brassy phrase, or love

Whispered a little out of tenderness,

She makes the willow shiver in the sun

For maidens who were wont to sit and gaze

Upon the grass, relinquished to their feet.

She causes boys to pile new plums and pears

On disregarded plate. The maidens taste

And stray impassioned in the littering leaves.

VI

Is there no change of death in paradise?Does ripe fruit never fall? Or do the boughs

Hang always heavy in that perfect sky,

Unchanging, yet so like our perishing earth,

With rivers like our own that seek for seas

They never find, the same receding shores

That never touch with inarticulate pang?

Why set the pear upon those river-banks

Or spice the shores with odors of the plum?

Alas, that they should wear our colors there,

The silken weavings of our afternoons,

And pick the strings of our insipid lutes!

Death is the mother of beauty, mystical,

Within whose burning bosom we devise

Our earthly mothers waiting, sleeplessly.

VII

Supple and turbulent, a ring of menShall chant in orgy on a summer morn

Their boisterous devotion to the sun,

Not as a god, but as a god might be,

Naked among them, like a savage source.

Their chant shall be a chant of paradise,

Out of their blood, returning to the sky;

And in their chant shall enter, voice by voice,

The windy lake wherein their lord delights,

The trees, like serafin, and echoing hills,

That choir among themselves long afterward.

They shall know well the heavenly fellowship

Of men that perish and of summer morn.

And whence they came and whither they shall go

The dew upon their feet shall manifest.

VIII

She hears, upon that water without sound,A voice that cries, "The tomb in Palestine

Is not the porch of spirits lingering.

It is the grave of Jesus, where he lay.''

We live in an old chaos of the sun,

Or an old dependency of day and night,

Or island solitude, unsponsored, free,

Of that wide water, inescapable.

Deer walk upon our mountains, and quail

Whistle about us their spontaneous cries;

Sweet berries ripen in the wilderness;

And, in the isolation of the sky,

At evening, casual flocks of pigeons make

Ambiguous undulations as they sink,

Downward to darkness, on extended wings.

Comment: Oh, Wallace Stevens! Why must you write such doozies? I've only read through this a couple of times. It's a poem I've never read before but it intrigues me because it is about belief". And I'm pretty sure Stevens was an atheist. Does anyone know what he means by "serafin"? Anyway, I write more on this later, but wanted to post to get further thoughts if anyone had any. I've been on the hunt for really great "nature" poems. I know they seem a dime a dozen in poetry, but if anybody has a particular nature poem they love, please post.

Friday, April 17, 2009

My Life's Calling

My life's calling, setting fires.

Here in a hearth so huge

I can stand inside and shove

the wood around with my

bare hands while church bells

deal the hours down through

the chimney. No more

woodcutter, creel for the fire

or architect, the five staves

pitched like rifles over stone.

But to be mistro-elemental.

The flute of clay playing

my breath that riles the flames,

the fire risen to such dreaming

sung once from landlords' attics.

Sung once the broken lyres,

seasoned and green.

Even the few things I might save,

my mother's letters,

locks of my children's hair

here handed over like the keys

to a foreclosure, my robes

remanded, and furniture

dragged out into the yard,

my bedsheets hoisted up the pine,

whereby the house sets sail.

And I am standing on a cliff

above the sea, a paper light,

a lantern. No longer mine

to count the wrecks.

Who rode the ships in ringing,

marrying rock the waters

storm to break the door,

looked through the fire, beheld

a clearing there. This is what

you are. What you've come to.

Comment: Poet Deborah Digges committed suicide last week. I had

never heard of Ms. Digges, but after reading her obituary and a few

of her poems I would like to learn more. Poet Sharon Olds was asked

to name a personally meaningful book of poetry and she named

Digges' last book of poetry Trapeze. I'm sorry to be posting all of

these morbid suicide notices (note to self: a disproportionate number

of poets either off themselves or live VERYtroubled lives), but on the

bright side these gifted people live on in their work. Digges also wrote

two memoirs. Fugitive Spring is about her childhood in Missouri,

growing up one of 10 children and The Stardust Lounge is about

her relationship with her teenage son.

I'm struggling with the middle of the poem:

The flute of clay playing

my breath that riles the flames,

the fire risen to such dreaming

sung once from landlords' attics.

Sung once the broken lyres,

seasoned and green.

I've read this over and over again and can't really picture or

comprehend what the poet is saying and how it relates to the

rest of the poem. What are "landlords' attics"? And why would

she say "flute of clay"? Is that literally the same as "clay flute"?

But the finale of the poem is quite fantastic. She marries

everyday things you can picture instantly like locks from her

children's hair with the dramatic sea/cliff imagery.

Thursday, April 16, 2009

Ode on Melancholy

No, no, go not to Lethe, neither twist

Wolf's-bane, tight-rooted, for its poisonous wine;

Nor suffer thy pale forehead to be kissed

By nightshade, ruby grape of Proserpine;

Make not your rosary of yew-berries,

Nor let the beetle nor the death-moth be

Your mournful Psyche, nor the downy owl

A partner in your sorrow's mysteries;

For shade to shade will come too drowsily,

And drown the wakeful anguish of the soul.

But when the melancholy fit shall fall

Sudden from heaven like a weeping cloud,

That fosters the droop-headed flowers all,

And hides the green hill in an April shroud;

Then glut thy sorrow on a morning rose,

Or on the rainbow of the salt sand-wave,

Or on the wealth of globed peonies;

Or if thy mistress some rich anger shows,

Imprison her soft hand, and let her rave,

And feed deep, deep upon her peerless eyes.

She dwells with Beauty -Beauty that must die;

And Joy, whose hand is ever at his lips

Bidding adieu; and aching Pleasure nigh,

Turning to poison while the bee-mouth sips:

Ay, in the very temple of Delight

Veiled Melancholy has her sovran shrine,

Though seen of none save him whose strenuous tongue

Can burst Joy's grape against his palate fine:

His soul shall taste the sadness of her might,

And be among her cloudy trophies hung.

(posted by Robin R.)

Wednesday, April 15, 2009

A Supermarket in California

What thoughts I have of you tonight, Walt Whitman, for I walked

down the sidestreets under the trees with a headache self-conscious

looking at the full moon.

In my hungry fatigue, and shopping for images, I went into the

neon fruit supermarket, dreaming of your enumerations!

What peaches and what penumbras! Whole families shopping at

night! Aisles full of husbands! Wives in the avocados, babies in the

tomatoes!--and you, García Lorca, what were you doing down by the

watermelons?

I saw you, Walt Whitman, childless, lonely old grubber, poking

among the meats in the refrigerator and eyeing the grocery boys.

I heard you asking questions of each: Who killed the pork chops?

What price bananas? Are you my Angel?

I wandered in and out of the brilliant stacks of cans following

you, and followed in my imagination by the store detective.

We strode down the open corridors together in our solitary fancy

tasting artichokes, possessing every frozen delicacy, and never pass-

ing the cashier.

Where are we going, Walt Whitman? The doors close in an hour.

Which way does your beard point tonight?

(I touch your book and dream of our odyssey in the supermarket

and feel absurd.)

Will we walk all night through solitary streets? The trees add

shade to shade, lights out in the houses, we'll both be lonely.

Will we stroll dreaming of the lost America of love past past blue auto-

mobiles in driveways, home to our silent cottage?

Ah, dear father, graybeard, lonely old courage-teacher, what

America did you have when Charon quite poling his ferry and you got

out on a smoking bank and stood watching the boat disappear on the

black waters of the Lethe?

--Berkeley, 1955

Comment: I cracked open a book edited by poet David Lehman called

Great American Prose Poems: From Poe to the Present. I read

through almost half of it and have to admit a lot of the prose poetry

I just didn't get. A lot of it felt like rambling. When I saw Ginsberg's

"A Supermarket in California" I felt as if I had found an old friend

--and was relieved! I don't know if someone else knows more about

prose poetry, but I found it almost more abstract than verse. Just

makes me want to know more. "Supermarket" is a great poem that most

English majors at one point or another probably have to read. I'm

going to re-read it a few more times. The thing that strikes me the most

about it is its tone. It grabs you just like much of Whitman grabs you.

Someone correct me if they know better, but I'm assuming this poem is

supposed to imitate Whitman's style and voice. An homage of sorts. It

has that intimate, urgent voice. Almost anthem like. I love how Ginsberg

imagines his predecessor as a goofy old man ogling young grocery boys

but also confides in Whitman as a fatherly figure: "Ah, dear father,

graybeard, lonely old courage-teacher, what America/did you have

when Charon quit poling his ferry and you got/out on a smoking bank

and stood watching the boat disappear on the/black waters of Lethe?".

This anthology of prose poetry also has Frank O'Hara's

"Meditations on an Emergency". I first became interested

in this poem because it was featured in the AMC show

"Mad Men". I will post it later and see what you all think.

To be honest, I didn't get it. I hate when I don't get it!

But as always, the website for the Academy of American Poets

has wonderful information on Allen Ginsberg and even features

an audio of him reading "Supermarket". It also has an

extensive biography.

Wednesday, April 8, 2009

Poems for Passover, part II.

by Marge Piercy

Flat you are as a door mat

and as homely.

No crust, no glaze, you lack

a cosmetic glow.

You break with a snap.

You are dry as a twig

split from an oak

in midwinter.

You are bumpy as a mud basin

in a drought.

Square as a slab of pavement,

you have no inside

to hide raisins or seeds.

You are pale as the full moon

pocked with craters.

What we see is what we get

honest, plain, dry

shining with nostalgia

as if baked with light

instead of heat.

The bread of flight and haste

In the mouth you

promise, home.

Comment: This poem pretty much describes matzah perfectly! Poor matzah. It's dry and flavorless and yet it makes yummy, yummy soup. I always get nostalgic this time of the year. Not for Easter, but for Passover. My immediate family is not very religious but we always went over to my Aunt's house for Passover Seder. In fact, it's only been in the last five years where I haven't celebrated Passover. Even in college and in New York, I would travel back to New Jersey for at least one night. It was a very special holiday because my Aunt made it a special one for all of us. Anyway, even if you don't observe it, I thougth these two poems were short and sweet and helped me fondly remember aspects of the holiday. I was actually going to post a poem I wrote in college about Passover Seder, but after reading it realized it wasn't very good. I might actually now (nearly ten years later) do the revisions the poetry teacher suggested!

Poems for Passover, part I.

| A Newborn Girl at Passover | ||

| by Nan Cohen | ||

Consider one apricot in a basket of them. It is very much like all the apricots-- an individual already, skin and seed. Now think of this day. One you will probably forget. The next breath you take, a long drink of air. Holiday or not, it doesn't matter. A child is born and doesn't know what day it is. The particular joy in my heart she cannot imagine. The taste of apricots is in store for her. | ||

| | ||

Wednesday, April 1, 2009

A simple truth...

If you are looking for a truly funny film, rent Hamlet 2. The film is set in Tucson, Arizona and is about an actor cum high school drama teacher, Dana Marschz, who writes and directs the sequel to Hamlet. The sequel, of course, is a musical extravaganza. Although, the musical is at first met with vehement opposition (the show stopper, for example, is a song called"Rock Me Sexy Jesus"), the show ends up being a critical success and goes straight to Broadway. Marschz triumphantly takes his students to New York to star in the hit show. In the last scene of the movie, his student Chuy declares his love of New York and Marschz replies with complete conviction:

"Chuy, you're going to have a magical life. Because no matter where you go, it's always going to be better than Tucson."

I feel blessed in the same way having lived in Dallas. Low expectations are actually a gift. When anything positive happens you're always surprised and delighted.

Sylvia Plath's son committs suicide

Has anyone read Sylvia Plath or Ted Hughes? Apparently, their daughter is also a poet. If you know of anything worth reading, please do post.

Below is poem Sylvia Plath wrote about her son shortly before her death. It's quite beautiful and makes me want to read more of her work:

Nick and the Candlestick

I am a miner. The light burns blue.

Waxy stalactites

Drip and thicken, tears

The earthen womb

Exudes from its dead boredom.

Black bat airs

Wrap me, raggy shawls,

Cold homicides.

They weld to me like plums.

Old cave of calcium

Icicles, old echoer.

Even the newts are white,

Those holy Joes.

And the fish, the fish -

Christ! they are panes of ice,

A vice of knives,

A piranha

Religion, drinking

Its first communion out of my live toes.

The candle

Gulps and recovers its small altitude,

Its yellows hearten.

O love, how did you get here?

O embryo

Remembering, even in sleep,

Your crossed position.

The blood blooms clean

In you, ruby.

The pain

You wake to is not yours.

Love, love,

I have hung our cave with roses,

With soft rugs -

The last of Victoriana.

Let the stars

Plummet to their dark address,

Let the mercuric

Atoms that cripple drip

Into the terrible well,

You are the one

Solid the spaces lean on, envious.

You are the baby in the barn.

Children at play

Another photo of Helen Levitt's, taken around 1952. I think this was in Spanish Harlem but am not sure. This photo makes me wistful for the "good ol' days." I wonder if children still play like this. These children look so absorbed in with they're doing. When I was kid I just remember going from house to house with my brother and the neighborhood kids. Thick as thieves, playing and roaming without any supervision.

I love too how there is so much life going on around the children. The photo is full of vitality and dynamism.